THE RESPONSIBILITY OF THE ORDINARY: An interview with Sheng Qi

by Michèle Vicat

Sheng Qi, photographed by William Dowell © 2011 |

Sheng Qi attracted international attention at the landmark exhibition « Between Past and Future – New Photography and Video from China » held in New York in 2004 at the International Center of Photography and the Asia Society. The Catalog's cover shows a photograph that would become the central icon of Sheng Qi's interpretation of history. In the aftermath of the crack down on Tian'anmen Square on the 4th of June 1989, Sheng Qi cut off the little finger of his left hand as a gesture of defiance to China's central government. The aspirations of an entire generation fell to pieces. The protesters may have wanted too much too fast, or they had been misled by the government's rhetoric and they had failed to understand what was really at stake.

Today, Sheng Qi relies on painting as a medium to portray the tears of ordinary people in China. His iconography uses the official photographs published by Xinhua and other sources to tell how people's dreams may still be out of reach today and their disappointments still too real.

We were lucky to be able to interview Sheng Qi just before the opening of his show at the Galerie Daniel Besseiche in Geneva. Not much time, but enough to get a brief glimpse of his story. We invite you to follow some of his observations.

You used to focus on photography. Do you still shoot photographs today?

Not for the moment.

The photographs that show your hand are very strong. Especially because of the hand missing a finger and the small photograph in black and white against the red background. They form a dialogue between your own story and the history of China. The lines in these photos are very sharp. But, when I look at the paintings dealing with the same subject, the feeling is quite different because of the dripping. Could you explain why you went from a photograph on which everything is so sharp to a more blurry effect in painting?

"Aunt," photograph, 120cm x 80 cm, 2000 © Sheng Qi

|

|

"My Left Hand Yellow," acrylic on canvas, 120cm x 80cm, 2009, courtesy of Galerie Daniel Besseiche-Genève |

When I did these photographs, I was just over 20 years old. They are memory of my action that goes back to 1989. Now, I am 46. My physical body is not as strong any more. In a way, physically, I am slowing down. The photographs are about history because they deal with the past (my action) and the future (my aspiration).

Today, I use dripping because when you see someone crying, when you see the rain outside or when you see the flow of the water in a river, then you see the passing of time at every single moment. That’s the reason I use the effect today because with the dripping you notice time passing. On all my images, I focus on the historical events.

There is a link between the way I paint today and the art education I received in China. We learned Russian realism and we had to incorporate that in propaganda. There is a connection for me with history, my part of history.

It seems that the photographs captured a personal commemoration of a specific moment in time. Today, it looks as though you are dealing more with time and the passage of memory.

In a way, it is something about sadness. It is a series about sadness, because you feel that time is never coming back.

In 1989, you were 24 years old, and you were just finishing your studies. What were your expectations at that time?

"Family on Bicycle," acrylic on canvas, 80cm x 100cm, 2007

courtesy of Galerie Daniel Beisseiche-Genève |

We grew up in a propaganda environment. Basically, we did not know about anything outside of China. Actually, we were born red and we grew up red. We did not know any other colors. This means that at 24 years old, I did not know anything about other colors. Not even pink! It was very difficult for artists because we are very sensitive about visuals. We were visually trained in a particular context. We did not know more than that. But, we knew something different was there. After the tragedy of 1989, I could not handle the situation.

I felt hopeless. So, I left the country as many other artists did. I went first to Italy, then to Paris, then to London.

How long did you stay in Europe?

Around ten years.

And why did you decide to go back to China?

It is very simple. I was homesick! I felt that I was slowly losing myself.

In what sense?

As an artist. I did my Masters degree in London. I saw so many different kinds of art: British art, American art, French art…I started to feel that I was different. I was Chinese, and I could not find any space for myself and for my art at that time in Europe. I did a performance at ICA in London (Institute of Contemporary Art), which is a very important center for the arts in England. I felt somehow alone there, because nobody cared about Chinese art at that time. I had a show there with Xu Bing among others. I believe it was a very strong show. The director of the art center was very supportive. But, outside of the center, nobody talked about the show.

When was the show?

In 1997.

The interest in contemporary Chinese art was nearly nonexistent in the West at that time.

Yes, that is true. But, I felt disappointed. I felt I was wasting my time in Europe. I decided to go back to China.

What did you learn as an artist in Europe that you were able to take back with you to China? I am not talking about technique here, but more about integration of stories or messages.

Social values. Social care. Social views.

Most of the Chinese artists in China are more interested in their own development. They are chasing an art form, painting, sculpture, photography, installation, video art…The point for them is what is fashionable in the art world at a certain time. I do not really care about that. I care about reality, not about an art form or an art technique. I am not following an academic path or an intellectual one just because it is in fashion. I have no interest in that.

"Blue Bikes," acrylic on canvas, 80cm x 120cm, 2008

courtesy of Galerie Daniel Besseiche-Genève |

So, when you came back to China with these values and ideals, how were you perceived? Did you have difficulties fitting into the art world and communicating your ideas?

It was difficult to fit in with the local values. The only people with whom I could share ideas and values were the artists who also lived abroad.

In general, it is very difficult for me to talk to “normal” Chinese people because they are not interested in what I am interested in.

If we look at the paintings that are in this show, we can see a lot of images dealing with the past and more specifically with Tian’anmen Square? What is your feeling today about Tian’anmen Square? Do you think that you will eventually go beyond this image?

"The Sun," acrylic on canvas, 100cm x 120cm, 2009 "The Sun," acrylic on canvas, 100cm x 120cm, 2009

courtesy of Galerie Daniel Besseiche-Genève

|

It is the center of politics in China. In a way, it is like Saint Paul’s cathedral in London. No one can ignore the place and the history attached to the place. As Chinese, no one can ignore the meaning of the Square. It is the center of power. I will continue to produce work around that Square for that reason. But, I am also looking for themes that are linked to this idea.

Today, what are your fields of exploration? Do you exclusively focus on painting or are you also interested in films, installations, performances?

What is your feeling about your personal advancement as an artist?

I am focusing on 3 issues: history, people, and politics. These 3 points are linked in all my work.

At the moment, I am focusing on my paintings. But, you never know. I have no plan. I am following the wind…

Two years ago, you had an exhibition at a gallery in Caochangdi (Beijing). People from the censorship bureau came and demanded that some of the paintings be removed from the wall. That does not create a sense of comfort for an artist living and working in China.

No, not at all. But, this happened several times already. The police came to my studio to visit it, as they put it. I think that is normal for a Chinese artist being in China. If you do not have problems with the authorities, it means that you are an official artist! There are so many official art departments in China including the famous academies of art. You learn how to be official. The learning of art is still very conventional in China.

How do you brake from that mould? What are the possibilities for younger artists today?

This is a big question. I do not know how to cooperate. But, I do not think that there are too many young artists who stand out. For my generation, people born in the 1960s, we had an ideal. We wanted to be an artist, to be an intellectual, to change something.

The generation born in the 1980s have become consumers. They are chasing different things. They are not interested in politics because they do not want to touch anything that would make their life uncomfortable. Many young artists are doing cartoon-like animation. It looks fun, lovely, the images are cute and lively. It is a different generation.

Do you have any contact with that generation?

No.

Artists of my generation or older ones, we had courage, we were brave, we took risks.

Are you teaching?

I used to do it in Beijing, but now, I have just moved my family to London. Our son is almost two years old. I will go back and forth between London and China myself. I want my son to have the freedom to learn and not to be raised in the Chinese educational system.

I am keeping a studio in Beijing, but in London I am renovating two garages as my studio where I will do smaller paintings.

Could you explain why some of your paintings work as a diptych in two different colors?

"Mourning" (Dyptich), acrylic on canvas, 120cm x 200cm, 2007

courtesy of Galerie Daniel Besseiche-Genève |

I try to use as little color as possible, because I know that less is more. That’s why I prefer to use black, white or grey for example. Black, white and grey work like traditional Chinese painting. They are the colors used for calligraphy. For a Chinese, this is the most basic kit we can use. This is also for me a way to link with the tradition of Chinese painting. Red is also used in traditional calligraphy. This is the color of the seal with the signature of the artist. As Chinese, we tie these colors together to express our traditional form of art. The other colors are there to create a balance. Sometimes, I will use some blue or green, or yellow. The other colors represent maybe 3% of the color I use in my work.

"Most Wanted RMB," acrylic on canvas, 80cm x 60cm, 2008

courtesy of Galerie Daniel Besseiche-Genève |

Right now, you essentially work with history and the effect of the past on memory. Are you planning in the future to work with more contemporary themes?

My recent work relates with powerful people in China, Hong Kong and Taiwan. People like Jacky Chan, Yao Ming. Entertainment stars and political stars. All these stars hold an RMB paper money in their hand. But, the money is like a traditional Chinese fan. This is my new work that I have not published yet.

The relationship between China, Hong Kong and Taiwan is very sensitive. The Chinese government always uses economics first to assert its power. The RMB, the currency, becomes in a way a weapon to slowly change the culture.

Now that you are back to London, how do you see the changes in China? Do you have any hope for China?

In fact, we, Chinese, are very positive about our country. In 15 years time, China will be different, better…we hope so!

How do you perceive your role as an artist in China?

It is a responsibility for the ordinary. Artists are not high in the society. We deal with the ordinary and that means having a sense of responsibility within the environment we live in.

Do you consider yourself a Chinese artist or an international artist?

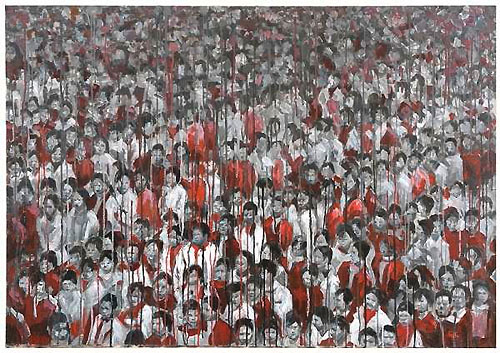

"People," acrylic on canvas, 90cm x 130cm, 2007

courtesy of Galerie Daniel Besseiche-Genève |

I think I am 100% Chinese! I wish I could be international, but I cannot go beyond the notion that I am Chinese and a Chinese artist. My work deals with history and social issues that are linked with China. I do not think that I can talk about other international issues. Today, one person in 5 in the world is Chinese. Nobody can ignore that fact. Whatever way Chinese behave today, you cannot ignore them. My work speaks about history and memory. It is in a way international.