| XUEFENG CHEN |  |

The Fragrance of Humanity

by Michèle Vicat

Xuefeng Chen in her studio, image © william dowell, 2014 |

«The question for me is what to do with contemporary art, » says Xuefeng Chen. “Today, everything is accepted in art: a bit of string, a bit of vomit, some excrements placed here and there…everything can be considered as contemporary art. I am not interested in that.” Xuefeng Chen is Chinese, but from Yunnan, far away from China’s mainstream. She looks at what is happening today in China: the rapid growth of the economy, the extravagance of consumerism, the changes in values. She tries to find her own place by looking for inspiration in the fact that she is a human being, a person who lived a “simple” life in a small village in Yunnan for the first 13 years of her existence. Today, she lives in France, in Lyon, far from China. “I feel that something is broken (in me), I have to build something new.” |

This poses a problem when it comes to exhibiting her work in China. The art world there sees her as going against current trends. Many artists try to use their creativity to be noticed, to make fast money, mainly by talking about the problems in China…all of that ignores China’s past and the key question: where does China’s culture really come from? Xuefeng Chen crosses over to the other side of the mirror to find these elements that are the source of what makes us human. In the West, her icons are Niki de Saint Phalle and Frida Kahlo, two women who brought inspiration and light to today’s problems. Both the role of women and Yunnan itself are crucial to the way the artist looks at the world and tries to integrate humanity into her own exploration.

What a shock when Xuefeng Chen left her mother to join her father who was living and working in the city of Kunming, the capital of Yunnan! Suddenly, there were rules, but rules of “civilization”: going to school, work hard to please the parents, enter into a system of obedience. She has erased that period of her life from her memory. Except that, from the time she was a child, she liked to draw and she learned that there was a school for drawing in the city. Her future began there. From the Institute of Art in Yunnan, she went to the Academy of Arts in Hangzhou, and finally arrived in Frankfurt in 2001. The turning point was her decision to settle down in France. France and its vision of itself as a cradle for the arts. France where she met her husband who is French. Her work now takes root in these two cultures, one in China and one in France. It is not a question of assimilating the differences, but of accepting the fact that the right mixture will emerge by itself. She considers herself to be a “métisse,” a blend of two cultures. The only choice is to build her own nest. Her father and mother are no longer in the equation. “I am what life has given to me and what it continues to give me.”

Anaana (which means “mother” in Inuit) explores the frontier between her childhood and her transformation into a woman. It is a sculpture that probes her inner self as well as what it is to be a human being. Where do we come from? Where does art comes from? Anaana might be a homage to the Venus of Willendorf, one of the most famous prehistoric steatopygous statuettes that were executed between 28,000 and 25,000 BC. Here too, the forms, quite schematic, give the impression that the artist has simply piled on lumps of plaster to exaggerate certain parts of the human body. The sculpture grows from the earth: the motifs that cover the legs are both foliage and scales. We are here at the beginning of humanity when our ancestors created myths about the origin of the earth and of the oceans. The monumentality of the work does not come from the size – although it is high: 2,20m. It comes from the spectacular cluster of breasts, a ceremonial jewel that completely overpowers us. It invites us to bury our face in its protuberances. Xuefeng Chen remembers when her daughter naturally suckled her breast, but eventually extended the suckling to her entire body. She realized that a breast is the universe for a small child: it is at the same time the sun and the moon. And there is the part of mystery, which is both universal and individual. We understand the world through stories that put us in touch with our past, a past so distant that we have nearly lost the connections. This sculpture is an open question for the artist: what was humanity at the beginning of time? When people saw the sun, they created a totem. Where does that creation come from and how can we pass on that message today? Anaana is Xuefeng Chen’s totem. The sculpture personifies the eponymous ancestor of every woman. It tells how our body changes, how nature sends new signals to our mind, today or a thousand years ago. The symbolic “mother” guides us from our own universe to the whole universe.

Xuefeng Chen carries in her memory the spirituality of the stories told orally in Yunnan. “It does not mean that people are religious,” she says. “It is like eating. Before eating, you prepare the table. It is natural, it is part of the habits of life.” From her mother, she learned to respect nature. From the people in villages, she learned the points that knit and bind these traditions together. Today, she links the mythology of her childhood to art while avoiding the caricatural vision of a past that must be resurrected. Embroidery helps her to start the journey. It may, at first, sound like an odd choice, especially since Xuefeng Chen was never interested in learning the technique, though it is an important tradition in Yunnan, where mothers used to embroider their daughters’ trousseaus when they were only three years old. The motifs and the bright colors evoke the luxuriance of the surrounding nature. Being in France, where the language and the culture are different, created the necessary distance to understand that embroidery was more a way of writing than a succession of points to achieve a pattern. She could then navigate her way through the heaviness of ancestral rules and codifications. “ I did not want to use a traditional technique just for the sake of preserving the technique or because it seemed pretty. Also, I did not want to mix East and West, the way most art does today in China. I followed a thread and the motifs came almost accidentally. I finally realized that it was in my blood.” Although the artist distances her from traditional motifs and colors, the meticulous gestures of sewing enables her to reconnect with an ancestral dialogue. Tradition is diluted today in China not only by commercialism that plays to tourism, but also because the country has lost its connections to traditional values. Chinese are not the only ones responsible for this. Westerners also play a role in encouraging cheap exoticism.

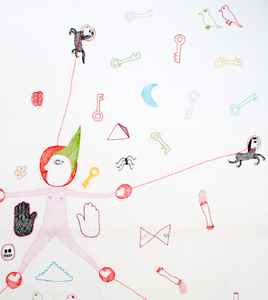

Xuefeng Chen incorporates the spirit of Yunnan into her own story. The two threads weave together in Deux Lunes, an embroidery she did in 2013. The white background absorbs soft colors. The embroidered points are delicate. Motifs are scattered against a background, which is nearly empty. As we enter into the piece, we notice here and there symbols nearly lost in the composition. Then, the strangeness of the dissociated elements begins to emerge…and the violence becomes apparent: a human figure is quartered. At that moment, she was reflecting on her status as a woman, a mother, an artist, a human being caught between parallel worlds. One moon is comprehensible. When there are two moons it means that we are facing many doors, even though we do not have the keys to open them. At least not yet. One element may lead to another, or not. Is it necessary to finish a task to start another? In real life, where is the opening? This work is a path to discovery. She tries to navigate these worlds that know her and those that she knows. These are the universes that have passed through her and continue to visit her.

Deux Lunes takes us back millions of years to when people started to symbolically understand the world that surrounded them. When our ancestors tried to find the keys to appease natural forces. They initiated a path to understand how and why they were human beings. Xuefeng Chen’s work takes us on the road back to that initial breath of life. “When you consider how art started,” she observes, “everything comes from the rituals of life and death. You find vessels, jewels, weapons, etc…in the tombs. Art comes from there and this is responsible for its richness. We have this in China, but we are not exploring this path. We look forward without understanding where we came from. So, for me, there are many doors to open in contemporary art.”

For her sculpture, L’Amoureuse, the inspiration came from a personal relationship. The model, quite small, represents a man who played an important emotional role in her life. The question is how to extrapolate the dimensions of a small model. Do you want to simply reproduce it much bigger? It is really a question of energy and not scale. How to bring the energy out of oneself? Xuefeng Chen goes back to her source by representing a grand spirit: a totem that allows her to distinguish dream from reality. The model is the story. The sculpture symbolizes the story. The spirit of that man comes to us when it is transformed into a cat, a big cat, present, solid as the eternal lover. The creature on his shoulders appreciates the metamorphosis: one would almost say that it purrs with pleasure. She has found her home…momentarily…before jumping to another spot that will allow her to pursue her search for the fragrances of humanity.

|

||||||||||||

Xuefeng Chen's "Accouchement", embroidery,

Xuefeng Chen's "Accouchement", embroidery,