|

CHINESE INDEPENDENT FILMMAKING: Freedom is a State of Mind

by Michèle Vicat

Kevin Lee, photograph by Michèle Vicat © 2012

|

China’s citizens have taken advantage of digital technology to capture the unofficial scenes of their daily lives. While the explosive growth of China’s commercial film market and booming TV production houses have caught the attention of investors in Hong Kong and elsewhere, lesser-known independent documentary filmmakers are discovering a more somber reality. It is a reality experienced by artists, writers, school teachers and peasants, a reality that is riddled with trash, the detritus of demolition, family quarrels, displacement, and taboo topics such as homosexuality and drug addiction, in short, everything that the Chinese government would like to move to the outskirts of the international consciousness.

At the margins of society, China’s independent filmmakers have allowed their cameras to film the flux of dirty water and monkey business. Their cameras record a different history, one that operates at the slower pace of a humanity excluded from the circles frequented by the jet set. They unconsciously map the overlooked details that sociologists, political and economic analysts and historians will eventually rely on to understand what has really taken place in China. These documents mirror the collective and individual consciousness on the road to democracy.

I accompanied Kevin Lee, a partner at dGenerate Films to the screening at MoMA (New York’s Museum of Modern Art) of "When the Bough Breaks," a 147-minute documentary, completed in 2011. The director, Ji Dan, one of China’s few female independent filmmakers, introduced her work as a “luxury, because I do not need to answer to anyone. Certainly not to the government.” She is the archetype of independent filmmakers. She explained, “I do not come from a film academy. Things come from my own intuition. I want to discover what is inside me. For me, a camera is important to see reality. We have buried a lot in China.”

I had talked earlier with Kevin Lee, who is also dGenerate Films’ VP for Programming and Education, about the current state of independent documentary films in China. Here is the interview.

What is dGenerate Films? How did you start? Why? What are your goals?

dGenerate Films is a leading distributor of Chinese independent films. We are mostly in North America, but we also promote these films throughout the world. We organize exhibitions and screenings. We distribute these films on DVDs and home video primarily through Reframe, a distribution channel created by the Tribeca Film Institute and Amazon. It was instrumental in helping us start our business.

Currently we have 40 films in our catalog. I am quite pleased with our progress. We started in 2008. Now we are entering our fourth year of operation. The founder is Karin Chien, an independent film producer. Around 2008, both she and I began to personally encounter independent filmmakers from China. They gave us a different outlook than American independent filmmaking, which tends to be a proving ground for more commercial and bigger budget films.

dGenerate Films’ co-founders are Karin Chien, Brent Hall and myself. Karin Chien is an independent film producer with a background in American independent films. My background is film criticism. I edit a blog for Indiewire, which is one of the leading independent websites for film. I also did some filmmaking, but my background is more in film appreciation, criticism and programming. Karin’s is more in production. We have a third partner, Brent Hall, who is more into starting businesses. He is VP of Marketing and Operations. He really helps us to run as a company. And there is Dan Chen who manages our daily operations.

cover for "1428," a film by Du Haibin |

You all have a background here in America?

Yes, we are all Chinese Americans. For us, culturally speaking, it is really interesting to learn about the films made in China. Within the context of filmmaking, it is fascinating, because independent filmmakers in China are very different from independent filmmakers in America or other countries. Chinese independent filmmakers really have a sense of mission, especially the documentary filmmakers. They tell stories that cannot be told in China’s mainstream media due to censorship and legal restrictions. It is the same for the narrative filmmakers. They handle topics dealing with social problems or crises. Usually, these topics are not discussed openly in Chinese media.

For that reason, their films have very limited distribution and sales prospects in China. When the restrictions prevent you from making money, then money is no longer a motivation for making films. But, these filmmakers still make films, which we find startling and very inspiring. The results are fascinating. There is a kind of freedom and fearlessness in these films, both in their subject matter and in their stylistic approach.

So, we are very excited about these movies. For Chinese independent filmmakers, there is a very limited chance to be distributed in China. We felt that we could create a film distribution stream and build an audience here in America.

You are primarily involved in distribution in America, but are you also involved in distribution in China?

Not so much. For legal and governmental reasons, it is risky to distribute in China. Also, there are fewer regulations about piracy. As a business, we cannot operate there. But, in America, there are tremendous opportunities to find an audience that can discover these movies and get excited about them.

What is the audience here?

Very quickly, we identified the primary audience, which is more cultural and academic: museums, universities, cultural institutions that are really trying to promote China as a cultural, artistic and social subject. We work closely with MoMA, The Asia Society, the China Institute and also with schools that have very good Chinese studies programs like Columbia, New York University, Harvard, Stanford, and so on.

The first couple of years, we really built the network. We found the people who would be interested in this kind of film, and we educated them about these films. It was also a way of giving access to these films. So, finally, we created a system in which the films could be brought from China and distributed here. It is important for people to have access to these movies. We have expanded into home DVDs and online streaming video. We have partnered with a number of online platforms including Reframe, Netflix, Fandor and Mubi.

scene from Du Haibin's film "1428" |

How do people react to these documentaries?

It is eye opening. In the Chinese media, you would not get any feed back for these films or for the topics they deal with. For example, the Chinese media do not deal with the problem of migrant workers, pollution, the environment, homelessness and drug abuse…all sorts of issues that challenge Chinese society now. In America, the media does deal with these problems in China, but the perspective is always a western perspective.

What is interesting about these films is that they are by Chinese citizens who have become filmmakers. Their perspective is completely different. You really feel like you are watching from the inside, through the eyes of people who are personally invested. It is not a topical story, a sensational story that attracts western stereotypes about China. It is actually a very thorough, three-dimensional experience. You really get a sense of how these issues affect day-to-day life in China.

I find it fascinating. China is building an archive of its contemporary history. In Europe and in America, we have dealt with the same topics: migrant workers, people working in mines and factories going back to the nineteenth century. We have in fact very few documents about that early period.

That is an excellent point. Everything really exploded in the last ten years. There may have been a dozen independent documentaries made every year in the 1990s. Now, you have hundreds of films made every year, and the reason is that the technology has become more available, thanks to the digital revolution. Filmmakers are able to buy a digital video camera for a reasonable price at their local store and it shoots HD video. Suddenly, there is the equipment to make videos. That is one thing.

The other thing is where China is now in history. It is undergoing such dramatic transformations that from one year to the next you cannot recognize where you are. It has not only created a sense of alienation and cultural shock for these Chinese filmmakers, but for Chinese in general. That creates a real need for these documentaries, as you say, an archive, a record of the changes occurring in China for people to remember where they come from, not just socially, but morally and ethically. It is necessary to show how these changes are affecting people’s behavior and values.

Is the younger generation of filmmakers better educated today? Ten or twenty years ago, anybody could make a video without any background in filmmaking.

This is still the case today. You have to look at this from an historical point of view. For decades, China had really only one film school, the Beijing Film Academy. It was the only school until the 1990s, and it only accepted a few people. Then came the media and television schools. These are very professional schools, but they teach you how to make safe films. So, it was not until the equipment became available in the last ten to fifteen years that people could go on the field. The amateur movement came into existence. These are people who do not have a background in film, but they have the desire. Maybe their background is in fine arts or painting. If I look at dGenerate Films’ catalog and I look at the directors, I see one artist who was a calligrapher, another who was a news reporter, another who was a teacher…they had no background in filmmaking at all. But, they all became interested in telling a story, usually a documentary story. It could be fascination with homeless people in Shanghai and why no one cares about them. Why were no movies made about them? So, these independent filmmakers become fascinated by the story that has not been told. It just requires a video camera and to start filming! I think that the main motivation and the main aesthetic are just to record, to be a witness and to capture reality. As time passes and you get more footage, a structure starts to take shape, a character emerges. It is very organic. There is no formula that has been applied from the beginning. It is a kind of film that discovers itself, that discovers the process as it is being made. As a result the films are very natural, very authentic.

Something different from the West, where we have TV channels that specify the length of a documentary for example.

Sure, the established conventions. In China, there are no commercial venues for this kind of film, which makes the situation even freer. There is no real opportunity to show these films to a regular audience. It allows filmmakers to be more creative. Now, this scene has evolved and there have been some standard films.

You also have to consider that each film brings more experience to the filmmaker and there is the desire to become more accomplished. It is not as though these filmmakers are doing films for themselves without wanting to show them to an audience. They care so much about the subject matter, about the experience. Of course, they want to share with an audience and they want to tell these stories about social problems that are affecting so many people in China. They would like to show their stories to as many Chinese they can. This is the challenge they are facing right now. They have established themselves as filmmakers. Now, the question is how can they deliver the story to an audience in China?

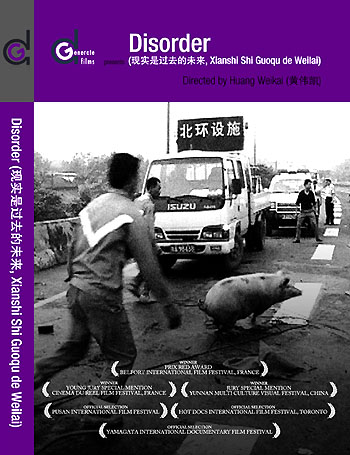

cover of "Disorder," a film by Huang Weikai |

What channels are available in China, especially after the detention of Ai WeiWei last year? The Songzhuang China Documentary Film Festival was canceled last year.

Yes, let’s talk about that, because that was one of the major sources for an audience. About ten years ago, there were film salons and forums, mainly in large urban areas like Beijing and Shanghai, where filmmakers invited their friends. Slowly, they started to learn about other filmmakers and they formed a network. Some blogs as well as some websites showed information about independent films on the Internet. Most of the time, these sites were discovered by accident. Someone was using a browser like Google, and found the films while looking for something else about movies. Gradually, an audience formed, virtually. Because these communities were able to form online, they were able to communicate with each other. Then the question was raised: how do we organize a festival? Invite people to come and watch a film together? It was a question to interconnect and have a different feeling about these films. That’s how the Songzhuang China Documentary Film Festival, the Beijing Independent Film Festival were created, as well as the Independent Film Festival in Nanjing and the Yunnan Multicultural Visual Festival. These are the major film festivals in China. But we are still talking about a very limited group, because maybe a hundred people come to these venues…this is not like a million people in China watching these movies. With the events of last year, there is a lot of pressure on these festivals not to show certain films, but if they cannot show these films, it is as though their purpose has been canceled.

It is an ongoing challenge. Aside from the film festivals, there are also on-line sharing networks like pirate DVDs for example. Nothing is legitimate, but in view of the situation, this is the best people can do. The fact that there are so many activities within these spaces is very remarkable. It shows the passion and the dedication of these filmmakers. With time and more attention, people will be aware that these filmmakers exist. With an increased awareness, there will be more demand to find the right channel to watch these movies. So much has already been accomplished that it leaves possibilities for the future.

Everybody agrees that the father figure of documentary in China is Wu Wenguang with « Bumming in Beijing: The Last Dreamers » (1989-1990). What is the evolution since then in terms of aesthetic and story telling? Is the younger generation telling a different story or is it doing it in another way?

|

|

scenes from Huang Weikai's film "Disorder" |

Obviously, Wu Wenguang is the key figure. Very much a first person-type of director, very much into personal stories and also into his own role as a filmmaker and as a protagonist in the story he is filming. He has set a very important paradigm or model that many filmmakers are following today. There is also another movement, or should I say aesthetic, which is heavily influenced by Frederick Wiseman’s school as well as the Shinsuke Ogawa’s school of filmmaking. Ironically, Wu Wenguang has a part in this, because he made the first independent film that was recognized outside of China. So, he was invited at this prestigious festival, the Yamagata International Documentary Film Festival. It is there that he, as well as other Chinese filmmakers, encountered the films of Frederick Wiseman and Ogawa. They were very deeply impressed by this kind of objective, observational approach of looking not at people, but at social institutions and how people are processed or affected by them. That really resonated with their experience of living in China with its powerful institutions. They realized that if they could direct the camera at these institutions in action, we could learn much about how they work and how they influence people’s lives. This approach of pure observation of people and institutions became the aesthetic that many Chinese filmmakers adopted. I think that Chinese independent documentary filmmaking has really operated between these two poles, these two models: very personal or very social, very observant. It continues to evolve. I think that it is becoming more experimental in many ways. Now, we start to see documentaries that are using film footage in a very creative way. There is the film "Disorder," that is one of the most remarkable documentaries lately. The film director, Huang Weikai, collected more than one thousand amateur videos taken on the streets around Guangzhou. He was able to assemble them into a kind of city symphony format, but not like these old films such as, “Berlin: Symphony of a Great City” (1927). “Disorder” is very new, it is how digital video looks and feels. It is very disruptive. You get the feeling of absurdity and madness through the juxtaposition of images. It is one of the most exciting documentaries in the world these days. The way it is done shows how the counter-culture functions in China. It is a sharing-making experience, putting together amateur videos. The people knew each other and they showed their work to each other. The director put the work together and gave it its direction. Not a big budget production, at all, but very resourceful, very creative.

Let’s talk now about the documentary that we are going to see at MoMA. « When the Bough Breaks » was done by Ji Dan, one of the rare female filmmakers.

The filmmaker Ji Dan, photograph by Michèle Vicat © 2012

|

She is in her 40s and she has been making documentaries for more than 15 years. She is one of the most accomplished women filmmakers in China, especially in the world of documentaries. She started as a schoolteacher and became fascinated by the lives of people around her. She wanted to record them and she got a high-8 video camera. That was in the mid 1990s, before digital video cameras. Over time, she developed a style, which is quite similar to Frederick Wiseman’s observational style. She is very modest, humble. She is totally opposed to the first person type of filmmaking. The way she expresses herself is « my camera » as the first person. She is like a protagonist through the camera: people can feel what they see through the lens. It is very subtle, very much a woman’s point of view as opposed to a man’s point of view. She does not need to show herself. She can be in the background and still express her feelings and emotions.

This film, "When the Bough Breaks," was several years in the making. She was doing a project and got to know a migrant worker’s family that had moved from the inner part of China to the Beijing suburbs, where they lived as homeless people. In the film, they have a shack next to a construction site. The reason for that is that the family has four children, three daughters including twin daughters and a boy, and it is being punished because of the one-child policy. The family cannot enter into the administrative system. They have to raise their children as homeless. The older daughter had gone missing, probably into sex traffic. The family asked the filmmaker, Ji Dan, to try to find her. In the process, something else happens. The younger children start to face their own crisis: the family has no money; can they continue to go to school? As migrant workers they cannot go to a normal school in Beijing, because they are not legal residents of the city. They have to go to a private school for migrant workers. They try to pay for that, but after a while they run out of money. It causes a debate as only one child can continue to go to school. Most probably that would be the son, which is standard for China. The daughters resist this. They think that there should be a way for them all to continue their education. The film starts when the family is facing this crisis: who gets to continue to go to school?

You can see how the children fight to determine their future. ( for a review of the film, go to http://dgeneratefilms.com/China-today/review-when-the-bough-breaks/#more-8977)

How did Ji Dan find this family?

|

scenes from Ji Dan's film "When the Bough Breaks" |

She knew the family for seven years. She originally met them while filming a documentary for NHK, Japanese television, in 2004. She started to film the family for her documentary in 2009. The filming lasted for a whole year. During the year the family had to decide who would take the school entrance examination. That meant continuing education or becoming a day laborer. Ji Dan captured this very critical moment.

Her style is amazing. The intensity of the arguments between the members of the family is there with you. You are there in the room with them. Because she knew the family for so many years, she was able to build a relationship with them, so they could become comfortable.

This film shows how skillful and accomplished these directors are. Not only because of the work with the camera, but because there is a human quality in the filmmaking, especially in documentary filmmaking.(see "A Conversation with Filmmaker Ji Dan" by Maya Eva Gunst Rudolph on

http://dgeneratefilms.com/China-today/cinematalk-a-conversation-with-ji-dan/#more-8900)

There is an important question regarding the relationship between the filmmaker and the people who are being filmed, especially when it takes years to do a documentary. Some of the Chinese documentaries took 5 to 10 years. How does the personal connection affect the documentary?

I think that we have to consider the commercial aspect. Filmmakers are not very affected by commercial interests. They do not have investors giving them a time limit to do a film. They do not have that kind of partnership. With Ji Dan, I do not even think that she has a regular job. She does that out of passion. She will take as long as she needs to follow a story and to develop it. It is a completely different model for filmmaking even for the world of independent filmmaking.

But my question was more about the kind of relationship that the filmmaker is establishing with the subject along these months or years of filming? How does that relationship affect filming?

In her case, people ask why some shots are so long, so slow. For her, it is the way she experiences people. She is there, just watching them. It is the way she experiences life: she is not active in the process. She is not planning to go here and there. She is in one spot and life happens in front of her. She observes it. It is a philosophy of how to relate to people. You can tell them what to do; you can mold them to the story you want to tell. This is the case with these reality shows in America and in Europe. It is all scripted.

Here, you follow these people and you go where life takes you. Your whole aesthetic approach is based on that attitude.

Does dGenerate Films helps filmmakers besides distribution?

It is a goal. Right now, our first goal is to help filmmakers to find a larger audience. This is a way to support their work on an ongoing basis.

Distribution is already a lot of work. Of course, we have also thought about production. Karin Chien is a film producer. She has the experience to do that. But, it is another level of commitment and we feel we need another company to do that. We feel that distribution is the most sensible way for us, for the moment, to give support to filmmakers. We are drawing an audience, which is creating an interest in the subject. That gives other parties an interest to invest in projects in the future. We are also creating a real revenue stream, because we sell the films for them, so money goes back to them. 50% of the sale goes to the filmmaker. That money is in their hands and they can use it to invest in future projects. It is our way to encourage them to keep making movies.

Which channels do you use to send them money?

Obviously, this is an issue we cannot talk about! Even getting the films from China is a challenge. We do not use the mail, because it will be inspected by customs. We have other ways to get the films.

Do you think that there is more freedom today for filmmakers in China?

cover of "The Transition Period," a film by Zhou Hao |

It is a very paradoxical situation. I have seen it first hand in China. Theoretically, you can do anything in China. Part of it is to know the right people. Part of it is not touching very sensitive things, and not openly opposing the government. It is the kind of thing that Ai WeiWei tried to test by being so public in his criticism. It was pushing the limits as far as possible. He is Ai WeiWei, a very well known artist internationally. Maybe he wanted to see how far he could push the system. Most Chinese artists do not have that kind of visibility, so they would never do such a thing. Again, it depends upon whom you know. If a filmmaker does something controversial, he or she will do it through some connections.

a scene from Zhou Hao's film "The Transition Period" |

For example, Zhou Hao, a filmmaker, made a film “The Transition Period” about government officials. He was able to get incredible access and to show scenes where an official was intimidating and threatening people in the community. How was he able to get these things? The official invited the filmmaker to make the movie, because he was very proud of himself. He was not thinking about how he would look!

On the other side of the power equation, people like Zhao Liang, who did "Petition," go to people who are fighting for their rights while nobody is listening to them. These people are already cast aside or abandoned by society. Nobody cares about their stories. So, it is also possible to tell their stories. It is a question of context and looking for the right opportunity.

It is amazing that filmmakers can do this kind of films…

|

|

| a scene of Zhao Liang's film "Petition" |

a scene of Zhao Liang's film "Petition" |

The problems only arise when you deal with distribution. Then, censorship comes in. It is not like the police will come to stop you doing what you want to do. There are so many things going on in China at the same time. But, when you try to reach a certain level of visibility or accessibility to an audience, then the mechanisms of censorship appear.

Things are still at the margin today. But, what is interesting with Ai WeiWei and what he has done –because it is so easy to get comfortable with these marginalized spaces- is to try to get people to watch what artists are doing. You need someone to push the boundaries and test them once in a while. That is the way that you get progress; it is never static. You have the margins and you have the main stream in China. There will always be this kind of dynamic.

What is the future of film festivals in China?

They are still going on, like the festival in Kunming. Although the last time was difficult, because the website was blocked. So, anyone outside of China could not learn what was happening there. Lots of what happened was reported afterwards. The Songzhuang festival is still a little bit in the air, but it looks like it will continue with some new directors. The Nanjing one has been able to keep the most stability, because it has cooperation from local authorities and local schools – three universities in Nanjing show the films.

Everybody is very careful and very diplomatic with the authorities in order to maintain these spaces. The film festivals all have different strategies and they all work on a different model. I do not know if one is better than the other, but it shows how different people try to cope with the same situation. It is very difficult to go beyond the officials and to show what you want and not play this hiding game all the time.

What is the relationship between filmmakers and the art world in China?

dGenerate Films was started with a Chinese artist, Ou Ning, who is a famous curator. He also made a couple of documentary films. One called "San Yuan Li" is a collective work done with several filmmakers. The other one, " Meishi Street," is kind of a citizen activist film, where he shows the streets in China that were demolished before the Olympics. He shows his films at MoMA, because he has a great relationship with the art world here in America. Museums invite him to show his films. This is how we discovered things we never saw before in China. We were fascinated by his subjects. We asked him if he had a distributor for his movies. We wanted to know if there were more films like his in China. The answer was positive, but he emphasized that there is no distribution for them –not in China and, at that time, not outside of China either. Thanks to him, we were able to link up with a lot of filmmakers. One thing we noticed then is that there is a strong relationship between filmmakers and the art world in China.

Li Xianting (right) at the 2011 Songzhuang Festival |

For example, Li Xianting is a famous art critic and he has personally founded this operation at Songzhuang to promote independent films in China. Many people who belong to the art world in China experienced this tremendous boom of Chinese art in the world market. Many artists became millionaires overnight! They created their own communities and they built their own studios that sometimes looked almost like Hollywood studios. It was a bubble that was helped by foreigners. It was an inflated reality that was beyond anyone’s expectation. I think that many artists felt that they were starting to lose touch with reality in China. They were in a bubble, but on the other hand they realized that reality around them was quite different. It created an interest, even a fascination for documentary films. Ai WeiWei is the perfect example of this, because he does these massive conceptual pieces, but at the same time he makes documentaries. He has done a dozen documentaries now, very much about social issues.

The Li Xianting’s Film Fund is an example of how the gains of the art world have been applied to developing filmmaking. For these independent filmmakers who do not have the right channel, it is crucial to have the support of the art world. It is just the opposite situation of having a lot of money and not knowing what to do with it. It is great having that as a system to support filmmaking. In that sense, the art world in China has been critical to develop these documentaries.

All images courtesy of dGenerate Films

All

material copyright 2012 by 3 dots water |

|