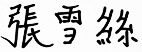

| CECILE CHONG |  |

When Everyday is Exotic

by Michèle Vicat

Cecile Chong in her studio, portrait by Frank Lei © 2012 |

Cecile Chong did not realize just how unique and complex her life experience had been until she came to New York. Even for New York, she was unusual. To begin with, she was born in Ecuador, was schooled in and spoke Spanish as her first language, and grew up surrounded by Chinese culture at home. The history of her family is deeply shaped by successive waves of immigration. In the late 1930s, her grandparents from her mother’s side arrived in Peru. They soon heard that there were better business opportunities further north. They moved to Ecuador, where both of Cecile Chong’s parents were born.

|

In 1948, Cecile’s maternal grandmother convinced her husband to move back to China where they built a house in her grandfather’s village near Guangzhou. A year later, the communist took over and the family could not leave. Cecile Chong’s mother was 9 years old at the time. At the age of 20, she married a Chinese who had also been born in Ecuador. The couple managed to leave China and return to Ecuador. It was already unusual that both Cecile Chong’s parents had gone back to China after being born abroad. It was even more unusual that they were able to return to their original birthplace after rediscovering their roots in China. Cecile Chong followed a similar path when her mother sent her and her sister to live with their grandmother in Macao. Cecile was 10 at the time and for the next five years she spoke Hakka with her Buddhist grandmother while receiving an education in Cantonese at a Catholic school. In 1979, she returned to Ecuador where she enrolled in an American high school in Quito. When she arrived in New York at the age of 19, she already knew that she wanted to be an artist. She studied studio art at Queens College before receiving a Masters degree in Education at Hunter College. Abstract art in oil and acrylic paintings helped her to realize that she wanted to understand how cultures relate to each other. New York encouraged her to make sense out of the different fragments of her life. It is really during her studies at the Parsons School of Design in New York that she was forced to go deeper than the routine banality of cross-cultural experiences shared by everyone in New York. Her teachers challenged her, asking her what she really wanted to express in her compositions. She had to reflect introspectively on what made her different, and also on her own, genuine and constructive narrative. The technique, encaustic, creating images with layers of hot wax, helped her to translate the waves of her experiences into a metaphorical, universal layering. The cultures, places, and images that she had lived became the source of her initiation into herself. It mirrored how she had learned to write in Cantonese. She had created stories in order to assimilate the characters. For example, she remembered the Chinese character for the number 4 as a window with two curtains. Encaustic is a very old technique and it challenged Cecile Chong to break through its frontiers into contemporary art. Encaustic painting, also known as hot wax painting, was used in the Fayum mummy portraits from Egypt (around 100-300 AD). The addition of particles of pigments to the richness of the wax texture gives portraits an ethereal look with enhanced density and luminosity. The technique was practiced by Jasper Johns in his famous « Flag » painting (1954-1955).

Using wax as a binder, Cecile Chong embeds and collages different materials, pigments, images, and objects into her compositions. As she explains in her thesis for the Parsons School, « all materials become cultural signifiers. » They not only refer to her childhood, but also to life in general and its preservation. And as life is never linear, memory connects the flux of emotions, relationships and existences, which inhabit the innermost depths of our psychological landscape. For the materials to become a cultural signifier, Cecile Chong applies twenty to thirty layers of wax on a wooden panel. Pigments, volcanic ash, gold leaf, silver and copper scraps as well as rubber shavings from tires, fake pearls, plywood, glass beads and parts of circuit boards are disciplined according to her will. Images of people and animals are borrowed from children’s books, coloring books, the Internet. They find a place in the composition according to the story she wants to tell. The materials come from places where she used to live and where she travels now. Through them, there is a dissemination of a personal history and the narrated stories are a re-interpretation of the ongoing story of humanity. « I go back to my childhood, » the artist told us in her studio. « But, I also feel that my work is part of belonging to the universal experience. In life, we connect with nature, but in the modern age we also connect with the Internet. » Fine volcanic ash from the eruption on November 4, 2002, of El Reventador in Ecuador is dissolved into the wax while images are melded between the encaustic. Nature and culture are not in opposition to each other.

In Well Balanced (2007), the artist brings together two improbable worlds. A barefoot Chinese man carries a balancing pole on his shoulder with two packages. He walks at its own pace in a landscape grandiosely represented in an Impressionist manner. On the other side of Cecile Chong’s composition, three children hold hands. They seem to be coming out from the landscape while the old man gives the impression that he is going into it. What is improbable is the juxtaposition of different times and different cultures. The children are Western while the man seems to be coming from another age that belongs to a traditional Chinese iconography. Cecile Chong took the image of the children from a Dutch vintage children’s book from the 1930s. The book belonged to her mother-in-law who received it when she was three. What the artist questions here is improbability and its relationship to history. Here, with Cecile Chong’s work, there are worlds, which would not normally come together. This is what she questions: what is normality? How can an artist take her own « normality » in charge and make it a tool for communication? The unusual is becoming our normal. It is up to us to find the codes of the unusual and to decode them. When Cecile Chong portrays a Chinese peasant crossing water and mountains, she goes back to her Chinese roots. The Sansui (water and mountain) is the Chinese landscape. The man’s eyes « meet » or sense the presence of the three children coming from a fairy tale, probably caught in a compromise between conformity and a fascination for the prohibited. Both explorations come together under an overwhelming, expansive sky. A sky bigger than the characters. This is the subtlety of the traditional Sansui. Man is present, but as a counterpoint. The juxtaposition of East and West is what Cecile Chong has experienced throughout life. At times, the juxtaposition has been natural or imposed, especially during her childhood, and at other times almost imperceptible. She likes to quote Rainer Maria Rilke: « A man’s true homeland is his childhood. »

Watched Pot (2009) again uses images borrowed from different places. Both subjects stare intensely at an incongruous object: a pot, a tiny pot, placed in the middle of the composition. Is this a cooking pot, a pot from which a genie will come out, the pot of knowledge, the pot of wonders? This is nearly irrelevant, because the story happens on the opposite sides of the pot. A woman stepping out of a classical Japanese print focuses her gaze on this strange object. The little boy on the other side has a posture that is especially tense: he is young, and possibly he wants to discover a secret that may emerge from the pot. Here too, the boy’s image is borrowed from a western children’s book. Both figures come from worlds apart, but they do not confront each other. They are there, present, each one with something to communicate. A little bit like the holographic image of Princess Leia in Star Wars, who appears suspended in space and fades in and out. She is trying to get a message through. Princess Leia, like our Japanese geisha, is on a pedestal, an illusionary presence that requires sensorial de-codification. Cecile Chong likes to group Asian adults with Western children. The improbable changes in conversation, which leads to cultural learning. « It may be surprising to know that I identify with the Western children, » the artist explains in her thesis. « This is because, in my case, I learned about my own ancestor’s culture as an outsider after moving to China from Ecuador. » The underlined emotional ramifications are echoed in the costume of the Japanese lady. Cecile Chong grew up in Quito in the 1970s. At that time the Chinese community, which consisted of 500 people, was the largest Asian group in the country. There were a few Japanese and Koreans. Japanese popular culture was big at that time. The concept of things cool, non-threatening like the Hello Kitty character, created in 1974, appealed to teens all over the world. Most of the household items were « Made in Japan ». Being an Asian in South America was confusing. When Cecile Chong mentioned that she was Chinese, people answered to her « yes, Chinese from Japan! » So, the Japanese woman in Watched Pot is a way to bring these realities together. The parallel existence of the two worlds is sumptuously enhanced by the amplitude of the sky. It is there that Cecile Chong uses her colored palette to reinforce the nearly silhouette forms of her characters. « The characters, » she wrote in her thesis, « intentionally lacked the dimension of color. I reserve the use of color for their environment. I see this as a metaphor for the idea that nature and environment are the source of much of our cultural context that ' shows through ' in the individual… By showing the characters as line figures I want them to be seen potentially as placeholders into which the viewers can project themselves ». There is always an empty space between the characters, not to separate them, but to leave us with the temptation to fill in the gap with our own story. The real tension is here, irresistibly attractive, meandering from one layer to the other one. A branch of a tree is often there, as if to prevent us to plunge into the abyss of the cosmos and to be lost forever. The sky and the trees, the rocks and the water, all elements of the nature that the artist intensely lived during her youth: in Ecuador, where the house of her childhood faced a deep valley with the Andes in the background, and in China, in the house of her grandmother where they sat outside to take their diner facing the HmGweiShan mountains. The sky was omnipresent during her childhood, and is a companion today in her studio in the heart of Manhattan!

There is an overall impression of comfort when you look at Cecile Chong’s paintings. This is probably due to the sense of smoothness created by the encaustic. When you see the actual work, there is a dimension that is missing in reproductions: you feel that you can almost taste her work…it is like savoring the apple of paradise lost! She, herself, compares the technical process to cooking. And this is how it feels when walking towards a table standing against the panoramic window of her studio at the Elizabeth Foundation for the Arts in New York. Cubes of wax wait to be plunged into a pan before melting from the heat of the stove. The resulting creamy substance is then applied on wood, layers upon layers. On the table, there is a jumble of equipment, including piled up boxes and jars with the material that the artist has gathered in various parts of the world. There are pigments from India and Morocco, pieces of circuit boards, beads from the Amazon…In that chaotic assortment, there might be fruits, snacks and candies that will eventually add touches of vibrant colors to the landscapes in her paintings. The bright orange in her composition, for instance, recalls a time when she ate mango snacks.

As in fables, unexpected protagonists appear suddenly in Cecile Chong’s paintings. Tiny people, nearly invisible surprise us when discovered and they raise questions. As in a cinema storyboard, it is up to us to notice the anecdotal in order to get the relevance of the whole story. The colorless thumb-like figures make us aware of new stories, other stories, which take place under other geographical and psychological latitudes. There is a crossing of paths and destinies here. The tiny figures, perched on tree branches or placed in a basket, symbolize Cecile Chong’s connection with South America and her questioning about nature versus nurture. « Are we the way we are because of our parents or our environment? » she asks us. « I wanted to have a South American component to my work. I thought about how the natives in the Andes are carrying their babies on their back. What if I were one of these babies? If I were born in Africa, what kind of person would I have become? Would I be different or would I be the same? » The swaddled babies, wrapped in large shawls, have no facial or physical features. They might be tiny, but their awkwardness makes them present, acting as cultural observers. They are called « guaguas » (pronounced ‘wahwah’), a Quechua and Aimara word used by natives of the Andes for a swaddled baby. Although not intentional, here too, there is the link between culture and food. The word « guagua » is also used to describe a bread shaped and decorated in the form of a baby.

Cecile Chong calls the metaphorical use of the « guaguas » her Tabula rasa. The theory of the Tabula rasa is that people are born without inherited knowledge. Experience, learning and perception form the basis of knowledge over time. Nurture takes precedence over nature. Tabula rasa means blank slate, and it is a reference to the wax tablets used by the Romans (the Roman Tabula) to take notes. It was logical for Cecile Chong to make the « guaguas » step out from her paintings. The idea came to her when she remembered a legend in South America: a baby who is swaddled correctly can stand on a table like a bottle! She took simple plastic bottles, wrapped them with plaster and burlap, and swaddled them with encaustic. Her new characters are bigger and play different roles when she moves them around in an installation. Still faceless and with colorless clothing, many interpretations are possible. They can be ghosts, babies, women with burkas…The ghost version is the one that speaks the most to the artist. People called her and her sister « The Ghosts’ Girls » or “gweimui” (the feminine version of “gweilo” meaning ghost) when they lived in the village of their grandmother in China. It was difficult for the two teens to convince the villagers that they were true Chinese. “Gweilo” was originally a racist term dating back to the sixteenth century, which referred to European sailors who the Chinese considered barbarians. Today, « gweilo » refers to foreigners in general.

Cecile Chong’s use of three-dimensional forms takes her to more experimental and ambitious levels. The sculptures can play together as a group or they can be individualized, carrying a more personal resonance and participation. The artist remembers the incident when kids in a school bus pointed at her saying « China, China, China ». She was in kindergarten in Ecuador. Back at home, she went to the bathroom, locked the door, climbed on the sink, and looked at herself in the mirror. « I saw a pair of eyes, a nose, a mouth, and I did not understand why the kids were pointing at me, » she still recalls with emotion. « I am not different. I do not know what they were talking about, » she pursues. So, the « guaguas » sculptures give testimony to her interrogation of herself about differences and the way they are encountered. Playing with her faceless actors, she can step back and interpret as many scenes she wants. The scenes of her internal voyage at the boundaries of her experience and perception as well as the scenes created and imposed by others.

It is in her relationship with others that she integrates the many places she comes from. People imagine her, build stories about her experiences, mold her into their own clichés. To deal with this imposed identity, strainers, beads and the mirror of her childhood are now incorporated in the Strainger Series, a penetrating play on words. A strainer is a mundane object. In the hands of Cecile Chong it becomes exotic. The idea of working with a strainer dates back from the time she was doing her Masters at the Parsons School. Her teachers wanted her to make something flashy and decadent while working in the context of the economical crisis. The combination of a strainer –an ordinary kitchen utensil- with beads and pearls –a luxurious personal ornament- allows Cecile Chong to explore the notion of cultural filters. By definition, a strainer is a device to retain solid pieces while the liquid passes through. It is a sort of alchemy of separation, filtering, screening. The result is a smooth preparation – a reminder of the encaustic. The mesh makes it easy to stitch the beads. A long, fastidious exorcism undertaken by the artist. A way to see how life takes uncertain paths. As a child and a teenager, she accepted what happened to her as normal. There was no difference between her and the little Ecuadorian girl seated next to her at school. They spoke Spanish. They shared the same games. She was equally at ease switching to Cantonese and watching a movie with the whole community in her grandmother’s village. For Cecile Chong, the attention required to pass the beads through the holes of the mesh of the strainer makes her wonder how we can live together while having been cut off from our roots. As she says, « Arguably, our cultures were formed in different places by the same human needs for survival and fulfillment. » But the way we see or perceive the world is fashioned by our natural, social, and cultural environments. The artist is telling us a personal narrative, a story that she herself has already filtered and is, in its turn as a boomerang effect, filtered by others.

The beads elevate the basic device to an awkward level of sophistication. Although keeping its general shape, the utensil nearly disappears under a profusion of tiny particles that come from all over the world. Natural and man-made materials that make us continuously cross the line between assimilation and acculturation. To underline our personal quest, Cecile Chong enjoys creating confusion by adding a mirror at the bottom of the strainers. We can see ourselves by looking at the strainer from the outside: the device becomes a full, elegant, mirror. An object of desire, a piece of finery reflecting the sophistication we build around ourselves. From the inside, the story is trickier. The mirror is there, but we do not have its reflective side. It is a blind mask. « It is like a progressive lens, » comments the artist. « With a lens you have to focus at a certain point and then you have to refocus on the side. Meaning that you can see the same thing, but the focusing is different. It has to do with how we perceive each other. How we do perceive cultures. »

Threads produce the invisible cohesion between the physical container and its psychological content. They create a whole new story by connecting the inside with the outside. The stitches are the undetectable links to a reality that cannot be seen from the outside, but, imperceptibly, patiently, and exhaustingly compose a maze of possibilities for us to discover, express, and share.

In their way, the threads create a bridge to the cabuya plant (see the detail of « Cinderella ») that the natives in the Andes use to make ropes. The new « Cinderella » passing through that unusual landscape transcends the copy, the imitation, the going back to the confrontation between East and West. Cecile Chong could have simply decided to go back to her ancestral roots in China, to immerse herself in stories that have, in any case, lost their cultural continuity. Her malleable Tabula rasa or Blank Slate connects us to the family of man and is the vehicle for the integration of her conflicting experiences. When she was in Macao as a young girl, her Buddhist grandmother asked her to burn incense before going to school. She refused to do that because she was attending a Catholic school and thought that God would be mad. Fifteen years later, she returned to Macao to visit her grandmother. She told her: “Hi, Grand Ma! Give me the incense!”

|

|||||||||||||||||