| Ma Desheng |  |

Stars and Stones

by Michèle Vicat

Ma Desheng photographed in his Paris studio by Michèle Vicat © 2011 |

Visitors to Ma Desheng’s studio in Paris are often surprised at the contradiction between the physical fragility of the artist who zips down the streets of his neighborhood in a wheelchair, and the impressive large format canvases stacked along the walls. It only takes a moment for Ma Desheng to propel us into his own expansive universe.

|

His eyes, dark, penetrating, constantly moving,

stand out in sharp contrast to the very pale complexion of his

angular face. His long silver hair is tousled and falls down

to his shoulders in fine undulations. He makes me think of a

seagull, tossing shells on a rock in an effort to extract the

substance that will enable him to survive, flying over the ocean

while taunting the waves. In the same way, Ma Desheng soars above

the currents of passing fashion.

Ma Desheng’s

generation had to work in factories during the day, but they

met at night in crowded rooms whose atmosphere was

thick with cigarette smoke and expressed their longing for

democracy and freedom of expression. A new culture was taking

shape by word

of mouth among painters, writers, sculptors, photographers

and poets. There was no public place for artists and intellectuals

to meet. A market for art did not exist. In China, art had

rarely

been an individual affair. People met in groups to play music,

to write poems, to do calligraphy. Art required symbiosis between

creative people. Except that this time, young artists were

not meeting in a superb retreat on a mountain or in an exquisite

garden

for inspiration. The hutongs (traditional houses in alleyways

in Beijing) became the preferred meeting place for youth without

money.

Ten years later, Wu Wenguang’s documentary Bumming in

Beijing: The Last Dreamers (Liulang

Beijing – Zuihou

de Mengxiangzhe)

From December

1978 to the end of 1979, the authorities, in keeping with their

agenda of liberalization, authorized people

to put

posters on what became known as the Wall of Democracy, a

long brick wall

located on Xidan Street, west of Tian’anmen Square.

Many dissidents believed the new line of the Communist Party,

which

exhorted people to “Seek the Truth from Facts.” The

diazibao, or large-character posters, called for political

reforms and even encouraged human rights. Ma Desheng describes

that wall

as “the wall of ideas created for political reasons

by Deng Xiaoping.” Ma Desheng continues, “We,

artists, we thought of creating another wall, a wall for

art. It was a good idea for

young Chinese artists who had no place to exhibit and to

show something different.” That is what people really

needed at that time in China. Something different. For thirty

years, they lived under

the same banner of uniformity: one leader, one ideology,

one costume, one book, one color. Ma Desheng recalls this

period: “We

met several times to find a name for our group. Under Mao,

the sun was taken as the symbol for unification. We thought

that

the stars could become an emblem of our individuality. Everyone

needs

an identity. We did not need one sun for everyone any more.”

The Stars received

the authorization to hang their work on the outside railings

of the Meishuguan, the National Art

Gallery in Beijing (now called the National Art Museum

of China). More

than

20 young artists participated in the Stars Art Exhibition that opened on September 27, 1979. Besides Ma Desheng and

Huang

Rui’s

work, the exhibition included art work by Ai Weiwei, Wang

Keping, Li Shuang, Qu Leilei, Shao Fei and others. Two

days later, the

exhibition was closed by the police for security reasons.

The themes developed by the artists were quite unusual

for a general public.

There were many representations of female nudes and some

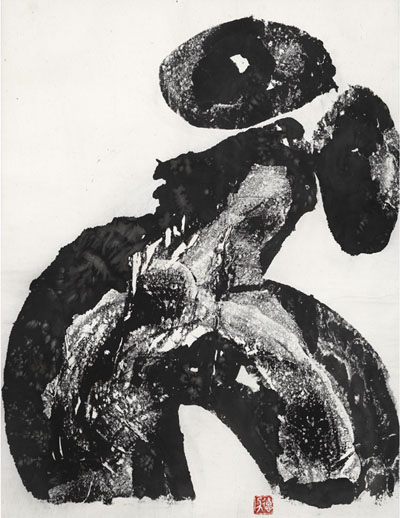

abstract work. Ma Desheng showed his woodblock prints.

Woodblock is a traditional

technique in China and Ma Desheng found his own style by

putting large amounts of black in the prints. Black was

a deliberate choice

against the red of the Cultural Revolution. “It was

not a question of technique,” Ma Desheng tells us. “I

never really liked technique as such. For me, the most

important thing

was to project the fire that I had inside me. We, as artists,

we had to be against something. I was young at that time

and I felt

that I had to do something against communism and against

the way people were used to expressing themselves.”

Vision juxtaposes

silence and explosion. The dark, sad, anguished faces of people

are imprisoned in a world that has no detail

and in which shouts are suppressed. A new world explodes

frenetically from a central point – the sun – to form an array of

possibilities. The stars become vessels for hope although they

do not seem to penetrate the darkness of the somber citadel…not

yet…we are in 1980.

It is haunting

to watch Ma Desheng writing the words “la

vie est toujours là” in my catalogue.

Every two to three words, he has to readjust the

pen between his fingers with

his teeth. The pen constantly slips. The strength

is not there. The muscles are weak, but the will

is tenacious. In 1992, a car

accident in Miami, Florida, forced Ma Desheng to

spend two years in hospitals and undergoing physical

reeducation. Today, his wheelchair

is covered with layers of paint: a living testimony

to his obstinacy and indomitable spirit. “After

the car accident, my hands lost their strength. My

gestures are no

longer very

precise.

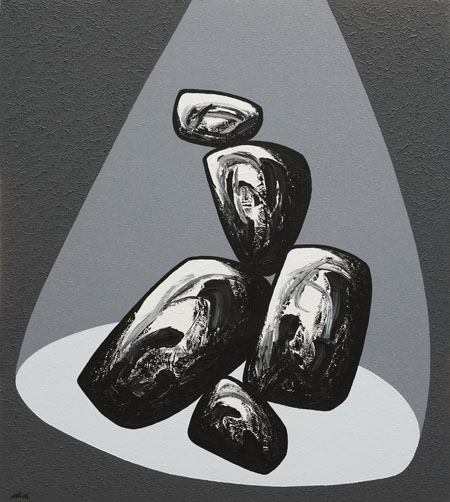

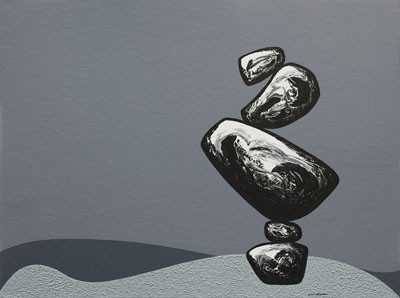

Before the accident, I was doing ink wash paintings

on paper. It is a

very sensitive technique. The least drop that falls

and it is over. You cannot retouch. Now, I use acrylics.

If something

goes

wrong,

I can scrape and redo the painting. With acrylics,

I

choose to paint stones.”

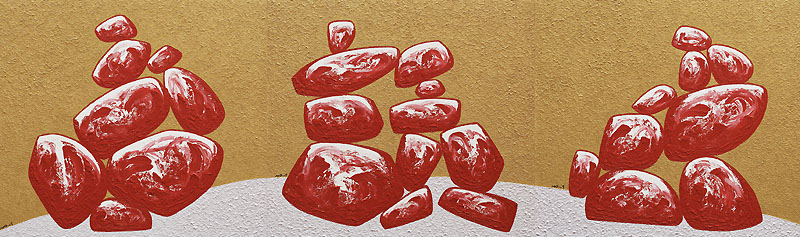

When looking

closely at the core of the stone, we can feel flesh and blood.

We can recompose a human

landscape

with

breasts, hips

and buttocks. The stone shelters “the fire of the volcano,” as

Ma Desheng likes to describe it. He makes us travel to the source

of the energy. He makes us re-discover the traditional Chinese

landscape in which the body is often represented as a mountain.

He makes us reflect on the notion of the body in a Taoist way,

beyond the material envelope, but included as part of the whole

human personality. In the foreword of the catalogue of the exhibition

on Ma Desheng that was held in 2006 at The University Museum and

Art Gallery at The University of Hong Kong, the curator, Catherine

Kwai, summarizes what has to be seen inside each stone: “ Having

lived a life of homelessness and misery, Ma has

let go his pertinacity and has become more easy-going.

With

a Daoist

mind, Ma has contemplated

and gained a fuller understanding of the nature

of

hidden things.”

The shapes represented by Ma Desheng take on a lightness, a life of their own. It is as if the stones have the ability to move around and to bounce like the small figures in video games for children. They float and it is up to us to recuperate them, to miss them or to go to another level. It is a question of passage between movement and inertia. It is an obligatory rite of passage to find the taste and the aroma of inertia as well as the tranquil fluidity of the movement. Ma Desheng begins a conversation, a conversation about the whole and the unique. The forces inside become part of our reveries. They form their own fantasy. We can almost imagine the stones acquiring a lightness and flying towards other worlds of whose existence we are just beginning to be aware. These stones are the metaphysical reflection of the stars with which we are finally able to unite. |

Ma

Desheng is also a poet...

|

Ma Desheng's Voguer (detail), Acrylic on Canvas, 150 x 200 cm, 2008. photograph by Nicolas Pfeiffer |

All material copyright 2011 by 3DotsWater