|

|

|

Welcome to the Desert of the Real

How

does an artist translate, represent and communicate the loss

of identity in a society that is no longer stable? Wang

Jianwei undertakes the challenge in Welcome to the Desert

of the Real, a play that constantly oscillates between performance,

videos and theater. In Symptom, the artist tries to understand China’s contradictions. “It is no longer the way it was in ancient China,” the artist told us during the rehearsal of his play at the Théâtre du Grütli in Geneva. “In ancient China, everything was very simple. Everything worked in a linear way. From one end of the line to the other, there was a common goal.” Today, the reality is less tangible. The artist takes his inspiration from uncertainty. The relationship that we have to people and to events is completely different now. The artist feels the need for a new approach in order to understand Chinese society, its culture and its problems. For him, the search for a method, for a way of representation, cannot be treated as a strict dichotomy: black versus white; pro versus con.

Welcome to the Desert of the Real was

presented in Basel, Zürich

and Geneva as part of a vast program on China offered this

year in Switzerland by the cultural organization Culturescapes

(www.culturescapes.ch).

The Théâtre du Grütli hosted Wang Jianwei’s

work for La Bâtie Festival de Genève this

September 2010.

Welcome to the Desert of the Real is

based on a short news story published in a Chinese magazine

about a 16-year old

boy, who

strangled his mother.

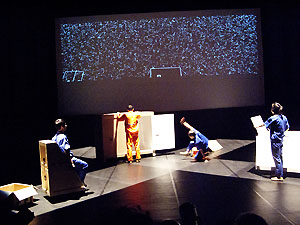

Meanwhile,

five actors emerge silently from wooden boxes. A hand appears

here, five fingers there, a head

and then

a foot,

a bottom

pushing the top of a box while a leg stretches, lifting

the side of another box. The body parts emerge and

appear in

our visual

field like icons on a video game. And you are lost

because you do not know which one is important, if

there is any

logical sequence

or not, if the game won’t virtually explode

in your hands. When the actors-dancers have reconstructed

their

body, they

move, as if they were running amok. Chopped and contorted

gestures, walking jerkily with no specific direction

as lost in the meanders

of the streets and ultimately of their mind. Hope

may

be there when they walk toward each other. But, at

the last

instant

of

an eventual meeting of eyes, they turn around and

continue their walk like puppets from which a cord

would have

been cut.

Beijing

hosted the world première of Welcome to the

Desert of the Real. Wang Jianwei was positively surprised

by the audience’s

reaction. Spectators connected the play with the recent dramatic

events that occurred at the technology giant Foxconn, a Taiwanese

company, which employs 900,000 workers all over China. Thirteen

young workers attempted or committed suicide between January

and May 2010. “ These are people who spend their day by

drilling holes in circuit boards and who have no relationship

with the person working next to them,” notes Wang Jianwei. “In

the dormitories, the person who is going to work is replaced

by someone else who immediately occupies the bed. These workers

never have a chance to talk with another person. Every day, they

lose more and more of their critical sense regarding life.” It

is a very high price to pay for China’s

development and for the gadgetization of the

West -- Foxconn

assembles our

iPods, iPads, iPhones, Dell computers and Apple

computers. (see the

blog below by a worker at Foxconn).

The

short news story, which provides the core theme of the play,

is symptomatic of all contemporary

societies. Communication,

space and time not only compete in the world

of

globalization, but they also demand that we

develop a new model

for reflection

outside of the “reality” used by states to promote

their own development models. Wang Jianwei believes this is the

duty of an artist, to ask questions even though they are complex.

Some spectators at the Théâtre du Grütli complained

that the play was too cerebral, too abstract to be within everyone’s

reach. They accused Wang Jianwei of being an elitist. These legitimate

concerns are central to an artist’s integrity

and involvement. A worker's blog published on China Digital Times (September 15, 2010) To die is the only way to testify that we ever lived Perhaps for the Foxconn employees and employees like us We, who are called nongmingong, rural migrant workers, in China, The use of death is simply that we were ever alive at all, And that while we lived, we had only despair.

More information on Desert of the Real and Wang Jianwei is available at http://www.wangjianwei.com |

||||||||||||

All material copyright 2010 by 3 dots water