Noticing

Xin Song’s taste for drawing, her mother sent her to

the local community center for children in the Haidian district

of the Zhongguanchun area in Beijing. At 14, Xin Song

was the youngest in the class. She learned calligraphy and

drawing during the weekends and summer vacation. Being with

older, more experienced children, taught her to overcome difficulty

and, later, gave her the self-confidence to apply to an art

school. In 1990, Xing Song majored in Fine Art at Beijing Haidian

Art School where she learned the basic tools of painting, drawing

and understanding color, all skills an artist needs to pursue

a career in art.

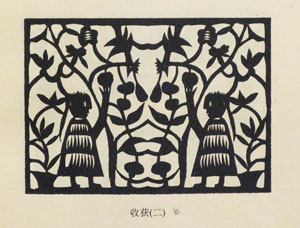

One of Xin Song's early paper-cuts

One of Xin Song's early paper-cuts |

“At

that time, I was 18, and I went to Yuan Ming Yuan where many

art students spent time doing landscapes, much like

the 19th century French Impressionists. The mother of one of

my teachers was a nurse and she had left a pair of surgical

scissors lying on a piece of paper. I took the scissors and

I started cutting the paper! People around me thought that

I knew paper-cut, but I was not familiar with the technique.” Intrigued,

she started to go to the library and discovered that paper-cut

is common in China and that different provinces have developed

different themes, some very humble like flowers, birds, children

playing and others more elaborate such as the Zodiac signs

or characters from the Beijing opera.

Xin Song had just graduated from the Fine Art School and she

spent the summer experimenting and enjoying paper-cut. It was,

as she said, “a happy time, a happy summer,” a

moment when she could let everything go and express herself

naturally. She was inspired by the simple life of the rural

areas: birds, fruits, fields, farmers working side by side,

rivers, took shape with the blades of her scissors following

the course of her imagination.

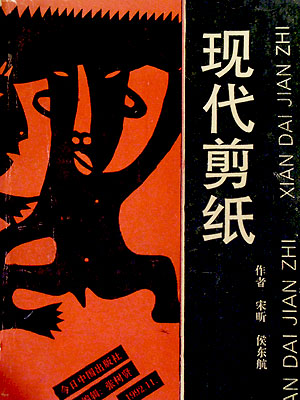

The cover of Xin Song's first book

The cover of Xin Song's first book

|

She did

almost 200 paper-cuts. A publisher noticed her drawings and

put them in a book, which

sold 7,500 copies. Today, the book is out of print and Xin

Song never learned what happened to the drawings that were

also bought by the publisher! The book opens with double

pages that form a story.

What Xin Song learned either by experimenting herself or,

later, by doing paper-cut with farmers, is to develop a

story in an unbroken line. The story is told with

the precision of the gesture: a slight mistake and everything has to be done

again, an extravagance in a poor economy.

It is at the Central Academy of Fine Arts (CAFA) in Beijing

that Xin Song fulfilled her dream of acquiring a deeper

knowledge of paper-cut. Chinese universities

began offering departments of folk art after the death of Mao Zedong. She was

extremely lucky to study with Lu Shengzhon, an artist who turned paper cutting

into a fine art. He prevented it from being submerged in the commercial production

for tourists. With Lu Shengzhon, Xin Song sensed that she could shape an enchanting

world that would not be frozen into tradition, but which could grow into an

artistic statement. The pulse of New York would provide

her that.

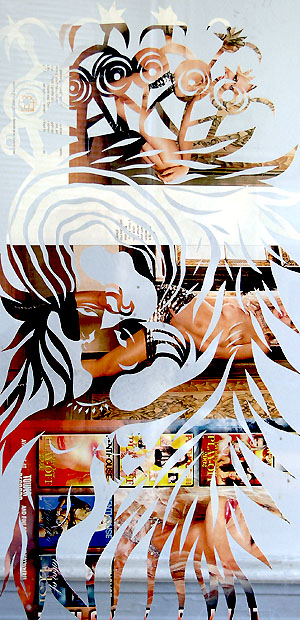

"Life=Sex?"

Series, Paper-cut with magazine collage, 12"x26", 2007,

© Xin Song |

“ Before, I usually used Chinese red paper or a plain white paper. When

I arrived in New York, I saw the magazines that people buy, read rapidly and

throw away. I thought I could recycle them and bring them back in another manner,” says

Xin Song.

The first difference with publications in China she saw was the pornographic

press. She was shocked to realize that these magazines were on sale in

public places. Children could see them, and she thought that they were

too young, too

innocent, to be exposed to that.

Xin Song saw this as a question rather

than a statement. She was curious to understand the difference. She started

to collect

porno magazines that she found in dumpsters and she cut the images, asking

herself in which way she could put the pieces together.

“When you look at these

magazines,” remarks Xin Song, “you see the sexual element right

away. When you cut the images, you cut them into elements. You select what

should be

in your story. You reflect on the way you were brought up and educated.

Not just me, as a Chinese, everybody. I think that by fragmenting the image,

I

can make

things more attractive, more seductive. People can see things differently

because it requires attention, another type of attention.”

"Life=Sex"

Series, Paper-cut with magazine collage, 36"x36", 2007,

© Xin Song |

Later,

Xin Song developed the Tree of

Life Series. “I transformed

the pornography into the Tree of Life, because making a life

is sexual, but after that, life

grows as a tree does,” she explains.

The Tree of Life is an important cultural and spiritual component in nearly

all cultures. The use of a tree as an element of connectivity is revealing

of our

times.

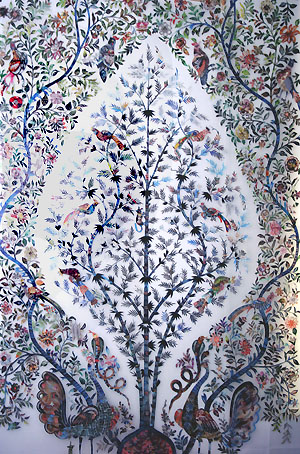

"Tree of Life" Series, Paper-cut with magazine collage,

© Xin Song |

Xin Song

now finds images in all sorts of magazines: travel, fashion, computer,

food and others. The images from these

magazines give the artist

a sense of what the public is being exposed to.

The myriad sources that she uses

embody the directions in which we are being uncontrollably

driven. The images belong to a world in which everything

has to move

quickly. We do not have much time to buy the latest design

before it looks out of date. Resolutely and as

a counter-offensive, it takes Xin Song two months

of work to finish a Tree of Life and the visual effect

is astonishing. From a distance, we can recognize

the branches, the leaves, a bird flying, a flower

in full bloom, peacocks snatching snakes. We can decide

to relax and to see it from a distance. It is peaceful.

But, our curiosity can also entice us to look

more closely and to discover that

the colors come from fragments of images and

texts. In our mind, we can try to recompose where the image

came

from and what the context was. It is a way

of

restructuring the world of consumerism and media.

But, deconstructed, we have another understanding that

has to be carefully deciphered.

“People can look at me as a woman who stays at home and spends her time

looking at magazines,” explains Xin Song. “But, for me, there is

more here. The media, the advertising companies work on the idea of a woman staying

at home, especially when she has children. I read the information in a different

way. I look at a written piece describing Cuban children using guns at an early

age. I can take it as pure information, a frightening information. But, what

is the real purpose of the magazine? I start to put these questions, these fragments

together…and there is a tree.”

In Xin Song’s vision of the Tree of Life there is a deep connection with

Chinese language in which one character represents a tree and doubling the same

character means forest. We have the “I” as

the center: we are a tree, then we become a forest

and people

become the

world. It is

the

essence

of the

cycle of life: things grow and take another configuration.

It was most probably a necessary step for Xin

Song to take. With

a tree,

one gets

roots and a balance;

something that she needed as a woman between

two worlds. The shape of the tree, composed of

different

parts

coming from

imaginary places, links

us

with the

notion of growth.

Detail of "Tree of Life" Series, © Xin Song

Detail of "Tree of Life" Series, © Xin Song |

|

Detail of "Tree of Life" Series, photo © Michèle Vicat

Detail of "Tree of Life" Series, photo © Michèle Vicat |

Not much was needed for Xin Song to take the

next step, to fragment even more finely the

information circulated through the media and

to space it out in

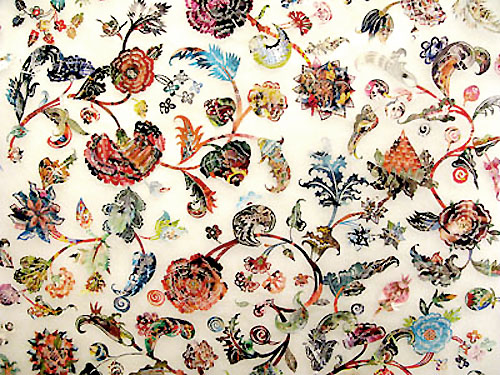

a visual field without any limit. Transformation is a series that brings us to

a solitary journey. The tree is no longer there

as a visual anchor. Xin Song found connections

with American folk art, and especially the

art of quilts,

which is also done mainly by women. Transformation is composed as a floral quilt whose

flowers and branches lead us first into a Garden

of Eden. The closer we get, the more we find

strange, even unsettling elements inside the

floral contours.

The artist wants us to look at things, but

not in a defined way. The patterns are composed

of fragments of objects from our contemporary

society, a society

that lives at a certain point in time.

"Transformation," Paper-cut with magazine collage, tracing

paper,65"x80", 2008, photograph © Michèle Vicat

"Transformation," Paper-cut with magazine collage, tracing

paper,65"x80", 2008, photograph © Michèle Vicat |

Today,

people are very oriented toward technology.

A computer represents technology. Take a

computer apart and you

fragment the technology. What do we need

exactly? Magazines may try to convince us

that

a computer was created to change the society

as well as the way we should look at our

self-improvement. But, what do we finally

take from that? What

the magazine

is doing is to vehicle an image of an era.

It is up to us to accept its interpretation

or reject it. It is a bit like negotiating

the translation of a word in a dictionary.

Several possible choices add to our perplexity.

Which one do we chose? Which term best captures

our intimate sense of the word? The paper-cut

images of

Xin Song are already a patchwork of our daily

visual, auditory, sensorial routines. Xin

Song extracts what touches, shocks and provokes

her the most. What she

offers

us is an aggregation of her vision, it is

the

vision that a bird has when it flies high

over a field.

Deatil

of "Transformation,"

Deatil

of "Transformation,"

photograph © Michèle Vicat |

The chocolate-flower,

a detail of Transformation (see image to the right),

captures Xin Song's thoughts about celebrations: “This

is something you produce for Easter,

for example. I think that in this world some people are rich

and can pay as much as a thousand of dollars for chocolate,

while other people cannot afford

basic food. Where is the frontier between luxury

and fundamental need? This is the

conversation I have with an image when I look at a magazine.

What does the image vehicle exactly?” The

question takes on its importance

when magazines are thrown away,

torn into

pieces,

reduced

into a pulp, then recomposed as

paper to lay out the icons of our

latest

trends. In Transformation, Xin

Song lays out

the

broken

pieces of our full illusions. |