| Zhang Hongtu "Blurred Boundaries" by Michèle Vicat |

Calligraphy by Liu Yongqin © 2010 |

|

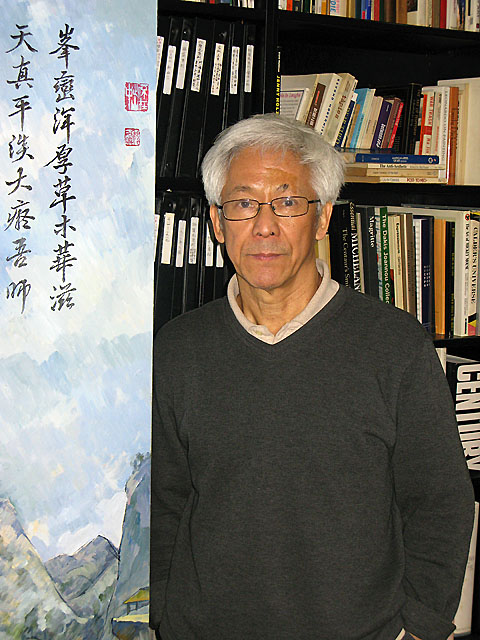

Portrait of Zhang Hongtu, photograph © Michèle Vicat, 2009 |

As a number of reviewers have pointed out, "blurred boundaries" is the expression that best expresses the way Zhang Hongtu moves back and forth from one culture to another and from one artistic genre to another. It is the quality of being blurred that allows us to weave cultural elements into each other and enables the spectator to travel in his imaginary world. His latest work, which he defines as “an on-going painting project, “ is a study of the essence of Chinese landscapes. In fact, the painter rejects the western term “landscape” and prefers to use the Chinese expression “shan-shui painting” because in Chinese art a “landscape” painting deals with the feeling for the interaction between shan (mountain) and shui (water). Water and mountain are the motifs of a traditional Chinese landscape. Shan-Shui is very symbolic because it represents the Chinese vision of what China is. In this spirit, Zhang Hongtu started in 1998 an exploration of both the classical idea of “shan-shui paintings” and western Impressionist and post-Impressionist techniques. | |

|

Fan-Kuan-Cézanne, oil on canvas, 64"x32", 1998 ©Zhang Hongtu |

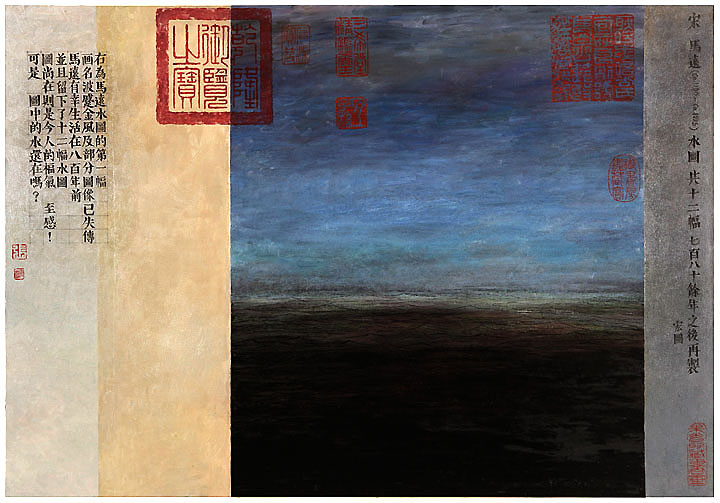

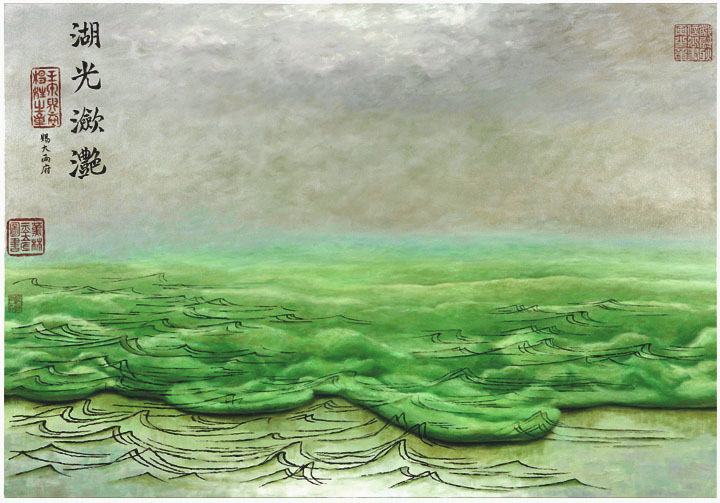

| Lately, Zhang Hongtu has gone even further by challenging our vision of beauty and reality. The artist is quite shocked by the transformation of nature today and more particularly of water. What was once tranquil and beautiful in nature is now transformed or even vanishing. In “Re-Make Ma Yuan's Water Album," a new series of twelve oil paintings on canvas done between 2007 and 2008, the painter’s inspiration goes back 780 years. In the paintings, he keeps the format and the general composition of the original work. He tries to find the boundaries between today and yesterday. Zhang Hongtu is interested in the nature of water today and what people are doing to it. “I think that half of the rivers in China are polluted with industrial waste,” Zhang Hongtu told us in an interview in his studio in Queens, New York, last March. “I am not a defender of rights of people but I am using my heart to express my ideas and to make things visually beautiful.” |

|

Re-Make of Ma Yuan's Water Album L, 780 years later, oil on canvas, 50"x72", 2008 ©Zhang Hongtu |

| If in his new paintings, the mountains are still intact (although in reality many hills in China are covered with a green mesh that contains tons of rubble, earth and sand dumped on the land as refuse by urban construction workers), it is because the end of the world is not yet here. It is because there is still a tension between past, present and future that alerts us to the disappearance of this perennial magical beauty that has defined the rules of the aesthetics in China. Water already carries chemical, human and occasionally radioactive waste. Waste is damaging the quality of water and Zhang Hongtu wants to alert us by using a vivid palette of colors to depict the water. Traditionally, old Chinese masters rarely colored the water. They relied on the texture of the paper itself. Because of that, it had a natural sense of flowing and created a peaceful feeling that we were going somewhere where we could find our identity. Zhang Hongtu shows the change through color. Today, water no longer has the color of the paper. He paints it green, or pink, or dark brown. The visual shock jars our retina. The world depicted is already dantesque and we have the sense that something in the composition is not working. Attention is required. The ink and brush strokes in traditional shan-shui paintings brought us to a subtle world of expected emotion. But, with Zhang Hongtu, there is a fine line between beauty and destruction. We are no longer confronted with an ideal world in which the visual parameters have been repeated generations after generations. But was this world ever ideal? When Monet charms us with a maritime landscape, a mist captures our sensibility. It looks beautiful, romantic but the mist is probably pollution. When Monet was painting, the mist and the mystery it created attracted people. But something was already wrong with nature. Industrial pollution had already begun. So, what is beauty and what is reality? When water becomes dark brown, beauty is challenged; the nature of the shan-shui painting is altered and this time not only for Chinese but for Westerners too. Beauty is not only for the eye. “In my new work, I take the beauty of an old work and I try to make beauty from the reality of today," Zhang Hongtu explains. "I still have a painting but something is changed inside the landscape, something that is a reflection on what is happening today.” Water and mountains are like the yin-yang. They interact in the painting in order to create the painting itself. A star, a tree, a boat, a human being can be added to balance the composition but it is the dialogue mountain-water/shan-shui that expresses nature, the ideal environment for Chinese. “Re-Make Ma Yuan” forces us to re-evaluate our approach to the artists’ work. Monet, Van Gogh, and Cézanne revisited by Zhang Hongtu tend to reshape our acceptance of the other. This is not an iconoclastic work. It is a work that juxtaposes cultures, creates an emotion, and makes us think about the notions of nature, image, and boundaries. |

| Blending the familiar and unfamiliar characterizes Zhang Hongtu’s work since his arrival in New York in 1982 at the age of 39. Before that, he tried to survive as an independent artist in China. A younger generation was starting to challenge the system. He was already older than many of the artists in the avant-garde. Born in 1943 in the northwestern province of Gansu, Zhang Hongtu had acquired a life-time experience at being different since his Muslim family was officially catalogued as “minority.” It put him at the margin of the Han society though the Chinese government tried to assimilate minorities to the official culture. In 1950, his family moved to Beijing where his father worked as a chief editor for “Chinese Muslim,” an official magazine. In 1957, the family was labeled as “Rightist,” an epithet similar to enemy of the people. |

Ping-Pong Mao, mixed media, 1995, ©Zhang Hongtu |

| From an early

age, Zhang Hongtu wanted to be an artist, but, there

was little future for him in China where artists

at the time were enrolled as propagandists. He chose

to leave rather than suffocate

in the stagnation of Socialist Realism. As a “CIA” person (Chinese Immigrant Artist) as he ironically defines himself, Zhang Hongtu had first to exorcize the influence of a society that deprived him of free expression and made it impossible to connect his artistic vision to his life. He created a name for himself in the international art world with his Mao series. What the general public in the West may consider as a joke or an assimilation to Pop Art, was for the artist a way to eliminate the load of the omnipresence of the Great Chairman. Growing up in the Muslim tradition of the non-representation of a human being, Zhang Hongtu’s generation was paradoxically flooded with Mao’s image. He recalls that even Muslim families had an image of the Chairman in the main room of their house. The notion of “image” was assimilated to the projection of power and it would have been considered sacrilegious to put Mao in any other context. Mao as the Quaker Oats Man, Mao in soy sauce, in popcorn, on a dress designed for Viviane Tam, even as a hole cut in the shape of Mao’s head out of a ping-pong table allowed the artist to emotionally exorcize “the authority of the image,” as he puts it. He could then explore other paths because guilt and pain were finally cast out. The Mao series helped Zhang Hongtu to pursue his exploration of the connections between artistic languages. He had in a sense no other choice. Having voluntarily left China, his Mao series made it impossible for him to return until 1997. By then, he no longer felt the shock of East versus West or the old versus the new. These former distinctions were no longer sharp. The road was open to his own future, to his own struggle. Memory, time, the self, and art itself became his new “blurred boundaries.” For more information about Zhang Hongtu and to see more of his work, visit his web site http://www.momao.com |

All material

copyright 2009 by 3 dots water